Osaka’s Instant Ramen Museum

Like most South Africans, I grew up snacking on Maggi Two Minute Noodles. Before the contamination scares and poison scandals and MSG controversy, the instant ramen favourite was a quick, tasty treat that took care of hunger pangs when our parents were away.

It was only as I got older (and subsequently wiser) that I began to realise the nutritious dish from my childhood was anything but. Still, I figured my taste buds had undergone the necessary training for my big move to Japan, where I’d get to try the real deal. It’s only unhealthy because it comes in a packet, right?

Wrong. After my first couple of samplings here, I realised that what others see as a delicious, warm bowl of comfort is actually just a swimming pool of oil and salt that has made my stomach lurch on more hangovers than I’d like to recall. Ramen is, please forgive me, kind of gross.

Millions of Japanese (and college students around the world) would disagree, of course: ramen is love, ramen is life. But what is it about the dish, exactly, that keeps people coming back for more? I went with Mark to a museum in Osaka dedicated entirely to the wheat noodles to find out.

The Momofuku Ando Instant Ramen Museum in Ikeda City is named after the inventor of the world’s first instant noodle product. Ando was born into a wealthy family in Taiwan and came to Japan in 1933 to study economics at Ritsumeikan University in Osaka. He became a Japanese citizen after graduating and established a small merchandising company.

But after the war, Ando was left without a job; his factory and offices had been destroyed in the air raids. On a walk around town one day, he stumbled upon a group of people waiting in line for something to eat at a makeshift ramen stall. The comfort food was a rare luxury for people in such depressing times – Japan was suffering a national food shortage.

“Peace will come to the world when there is enough food,” Ando thought to himself. He decided his new occupation would be finding a way to feed the country’s population.

Ando set to work in a small shack he built behind his home in Ikeda. His only criteria for the post-war food was that it tasted good, was safe and affordable, could be stored at room temperature and was easy to prepare. He experimented for an entire year without a day off, sleeping just 4 hours a night.

Finally, after throwing some noodles into tempura oil and discovering that frying dehydrated and perforated them perfectly, he developed a recipe that met his standards: noodles that could be quickly prepared and eaten simply by adding water.

He named his product Chicken Ramen (チキンラーメン) and opened a new company called Nissin Food Products. The noodles went on sale in 1958 and, although initially considered a luxury product, became an instant hit (pun absolutely intended).

Years later, on a business trip to the US, Ando watched supermarket customers split up blocks of noodles, prepare them in a paper cup and eat them with a fork. He realised that in order to advance his success, he needed to develop a product that appealed to different food customs. Soon after, Cup Noodle (カップヌードル) was born, catapulting instant ramen to international attention.

And Ando didn’t stop there. He continued to revolutionize international dietary culture by developing instant noodles that could be eaten in space. “Space Ram” was created especially for Japanese astronaut Soichi Noguchi’s 2005 trip on Discovery.

Two years later, Ando died of heart failure at the age of 96. He is said to have eaten instant ramen every day of his life.

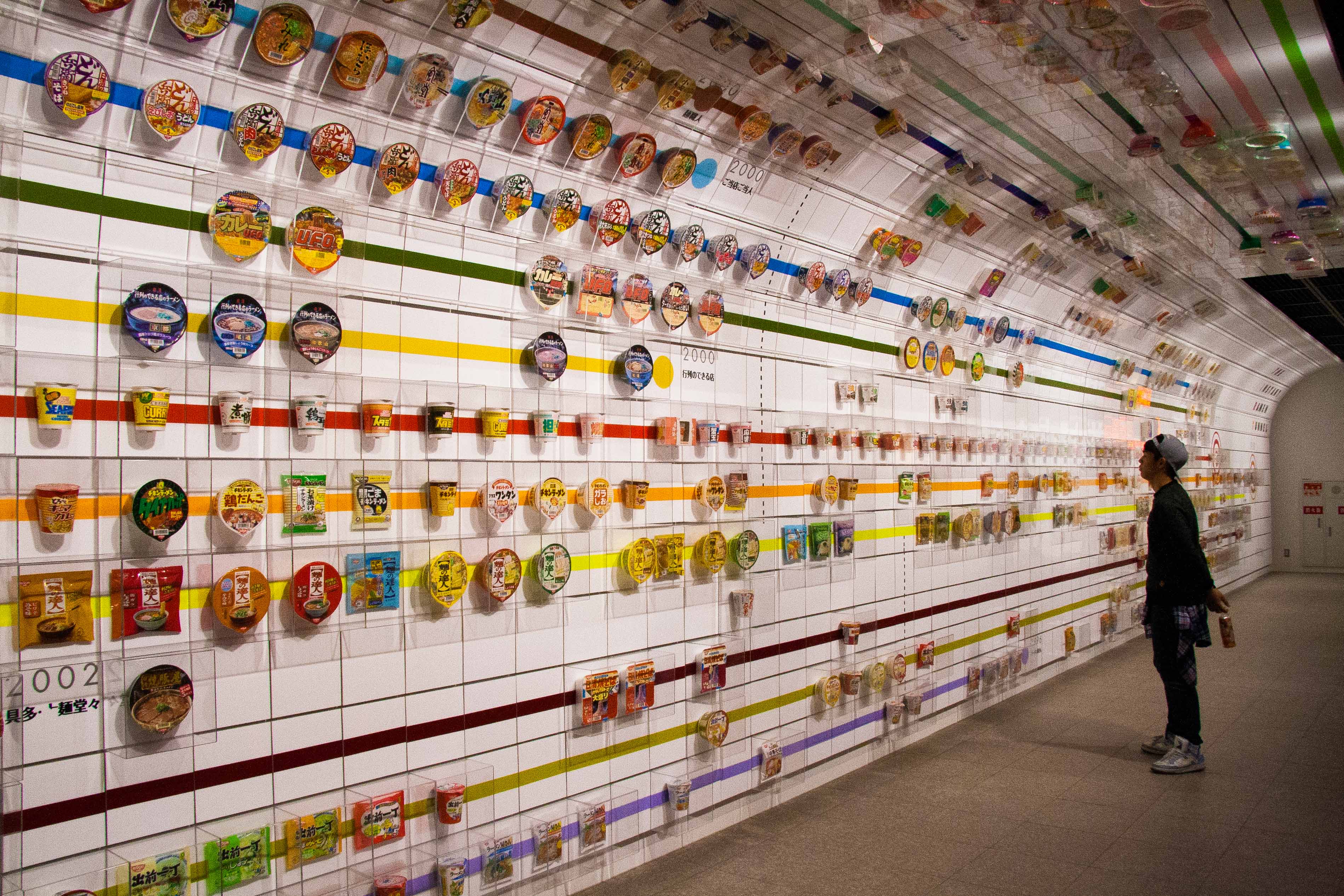

Visitors to the Instant Ramen Museum can learn about Ando and the history of his products through a wide range of interesting facilities and exhibits, including a replica of Ando’s research shack, a drama theatre, a tasting room and an Instant Noodles Tunnel, which traces the history of the instant ramen product line using over 800 product packages.

As soon as we stepped into the door, we were greeted by a staff member who handed us English brochures and gave us a quick explanation of the setup. We decided to borrow audio sets (2,000円 deposit per set, reimbursed on return) from the information counter in the gift shop. They turned out to be well worth it – without the narrations on the Birth of Chicken Ramen exhibit and the Cup Noodles Drama Theatre we’d have walked away with an eighth of the understanding we now had.

We headed to the My Cup Noodles Factory next to design our very own ramen. First, you purchase a cup for 300円($2.76;R41; €2.4) from the vending machine and then head over to a basin to wash your hands. At long tables, you can sit and pen out a design on the cup. I went with a panda because, you know, it has everything to do with Japan and ramen.

Next, you wait in a short line to the ‘factory’ where you can help place the cup over your bundle of noodles and then choose which soup flavour and toppings you want. The cup is then professionally sealed and handed back for you to shrink wrap it into a nifty air bag to take home.

The staff are incredibly friendly and patient – Mark and I joked that it was like a Ramen Disneyland – and although the exhibit is not very hands on, it was a lot of fun.

To truly experience the origin of instant noodles, you’ve got to make them yourself! Unfortunately, we didn’t realise that you had to make a reservation for the Chicken Ramen Factory workshop, where visitors get to do just that.

Luckily for us, the staff member who greeted us at the beginning of our tour said she would let us know if there were any cancellations. Well the ramen gods must have been on our side, because an hour later we were donning aprons and bandanas, ready to get to work.

After watching a short instructional video we were led with the rest of our group to a counter not unlike those you see in a cooking school. We kneaded the flour by hand, stretched out the dough using a noodle maker and then cut it into pieces. We then measured out 100g of noodles and placed them in a colander to be steam cooked. While we waited, we returned to our seats and designed another package (which meant another panda for me).

We then untangled the noodles, added seasoning and formed them into blocks, which were taken to a small kitchen where we watched them being flash-fried by staff members from behind a glass partition.

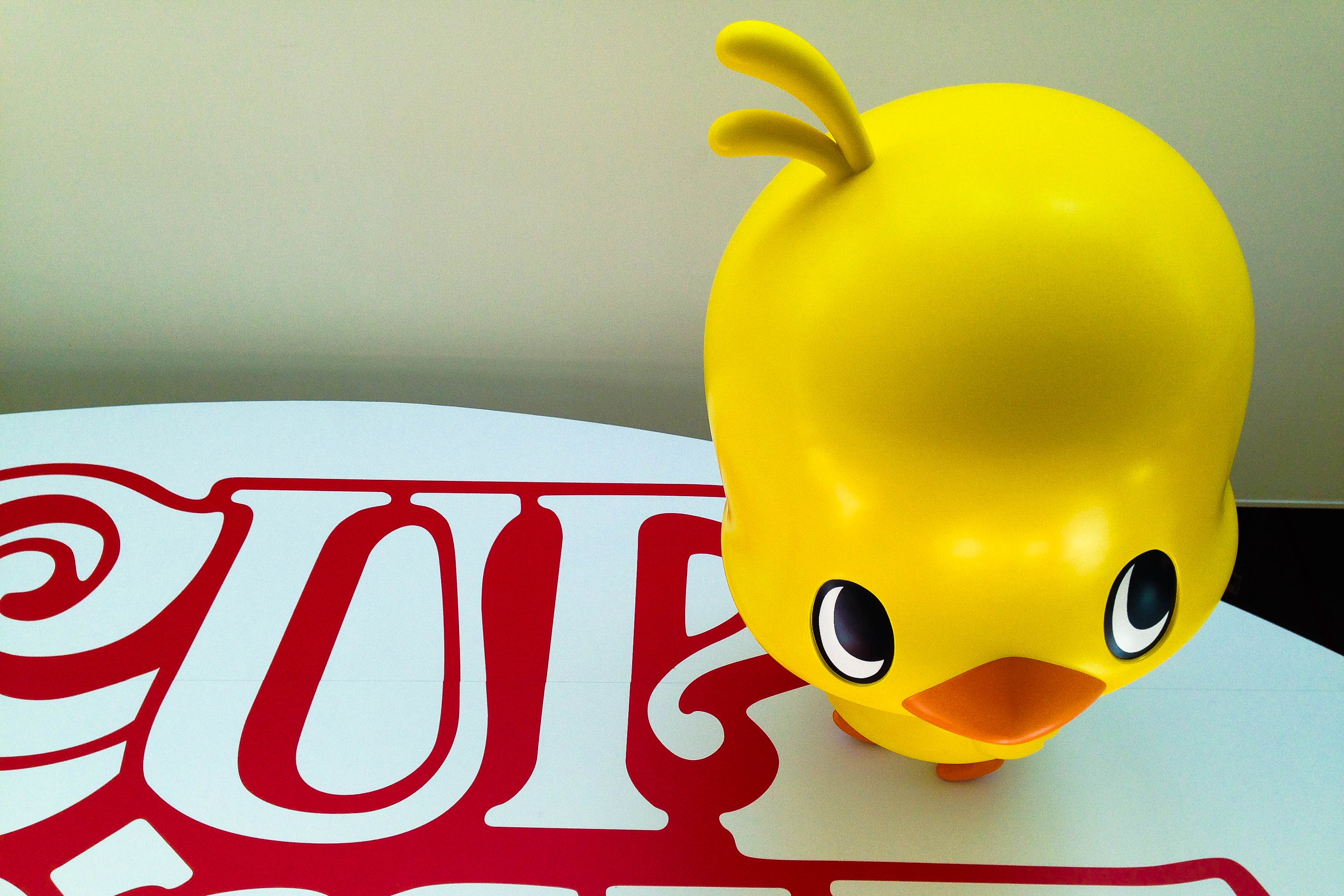

At the end, you get to take home your handmade, packaged noodles, an additional packet of Chicken Ramen, and the bandana, which is emblazoned with the museum’s mascot, Hiyoko-chan. For only 500円 for the whole experience, it was a pretty great deal.

I walked away from the museum with a new appreciation for Japan’s famous comfort food, and was actually excited to get home and try my very own ramen. When I did eventually open the packet, and crack off a piece of dry noodle to munch on while I waited for the hot water to do its trick, I forgot entirely why I stopped eating ramen to begin with. The familiar taste was meth to my tongue.

But halfway through the bowl, I stared down into the familiar oil and water mixture, felt nauseated, and remembered.

Hey, at least I tried.

This article is now available as a mobile app. Go to GPSmyCity to download the app for GPS-assisted travel directions to the attractions featured in this article.